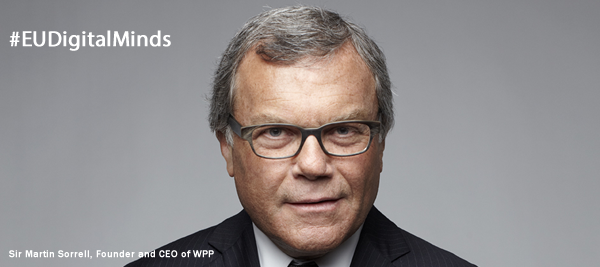

Sir Martin Sorrell, founder and CEO of WPP, challenges European leaders to bring coding into the classroom, and suggests other top tips for the digital age.

“Business leaders like to complain that institutions of government are slow, bureaucratic and blind to the “reality” of the marketplace,” writes Sorrell, “Politicians and civil servants respond that companies wouldn’t have a clue how to manage the complex web of competing demands and impossible choices that governments face.

(Both have a point.)

There is some common ground, though: everyone agrees that being lectured by someone on the other side of the fence is as counter – productive as it is offensive. So I’ll try to avoid doing that.

In Neelie’s invitation to contribute to this book, she wrote: “At a moment of transition, the old often has to give way to the new.” True, but in our business – and, I suspect, in most public bodies – managing the digital revolution is not as straightforward as all that. Few organisations, public or private sector, have the luxury of jettisoning their past.

Someone once said that moving from a traditional, “legacy” business model to one fit for the digital age is like changing the engines while the plane is still flying. It’s a perfect metaphor for what WPP has had to do.

When WPP entered this world in 1985 the web was only a gleam in Tim Berners-Lee’s eye. Even as we moved into the 21st century our digital revenues were still little more than a rounding error.

Today, digital represents more than a third of our $18 billion of revenues. Looking at the business more broadly, digital and interactive marketing, programmatic buying and big data account for about three quarters of turnover.

Reflecting on that journey (and for once that term is well used), I think Neelie’s diagnosis is correct: success in today’s world is not about technology or systems or clever bits of code. It is about outlook, mindset and culture.

Technological change isn’t just a constant: it’s accelerating. Technology will never again change as slowly as it does today.

Businesses and governments alike need organisations that are built to evolve on an ongoing basis. In that context, principles matter more than plans. We need principles to guide how we change; not plans to spell out what we change.

So, here are five guiding principles that apply equally to the worlds of commerce and government.

- Don’t wait for it to happen to you

Technological change is inevitable. Our response to it is not. Organisations that thrive in the digital age are those that take control of their own destinies, harnessing digital technology to work for them. The web and related technologies bring untold opportunities – but opportunities not taken rapidly turn into threats.

Amazon’s original model depended on selling books printed on paper. When the internet threatened to erode this market, Amazon created the Kindle. At the same time, bookshops went under in droves. Those booksellers could have created an e-reader. But they didn’t – they battled to defend the old order and maintain hard copy sales. A battle they don’t appear to be winning.

Not that long ago, the UK’s Auto Trader was a magazine for selling second-hand cars. Today it doesn’t print a single copy, but it remains one of the most successful classified advertising businesses in the world, recently valued at £1.8 billion.

Why? Because it saw which way the wind was blowing and began single-mindedly, even ruthlessly, transferring its operations from print to digital. Local newspapers, meanwhile, tried desperately to protect their motors revenues in print, and failed to innovate. These revenues (along with those from property and recruitment) disappeared forever to the web disruptors.

Institutions need to see digital as a positive enabler, not simply a threat or an inconvenience to be ignored for as long as possible. To quote the UN’s 2014 E-Government Survey, “citizens and businesses are demanding more open, transparent, accountable and effective governance” – via network-based technologies. Woe betide any elected official who fails to deliver this.

- Listen (and respond)

Digital technology creates new ways to listen to and understand consumers and citizens, paving the way towards more personalised public services.

Businesses have harnessed digital to create experiences that are more personal, more engaging and more effective. Many are using “big data” to automatically improve user experiences and to offer people the content or services most relevant to their needs. Wearable and connected devices will create new ways for people to communicate their needs to organisations.

The Netherlands, South Korea and Uruguay top the UN’s global league table for “e-participation” but innovation is happening the world over – from Slovenia’s “I suggest to the government” online tool and Morocco’s e-consultation platform to the Unicef-backed “Ureport”, a free, SMS-based system that allows young Ugandans to “speak out on what is happening in communities across the country and work together with other community leaders for positive change.”

In Cape Town, South Africa, citizens can report problems with water, electricity and other public services using a platform called “Lungisa” (“fix it” in isiXhosa) with responses from the relevant authorities communicated via web portal, SMS, USSD, Mxit and Facebook. As of October 2013, problems reported using Lungisa had a 73% resolution rate.

- Acquire a taste for risk (and a thicker skin to go with it)

One of the great clichés of modern business (imported from Silicon Valley) is the mantra of success-through-failure: “fail often”; “fail fast”; “fail better” etc.

For public officials that slogan is much more likely to be “for goodness’ sake don’t fail – but, if you do, fail as inconspicuously as possible.” Electorates, and the journalists who inform their views, are hardly forgiving when government initiatives go wrong.

That said, success in the digital age does need the right institutional attitude to failure and risk-taking, whatever the institution.

Not everything will work the first time. That needs organisational cultures with an appetite for controlled risk-taking – ones that can accept a reasonable failure rate, are prepared to stop activity that isn’t working and will learn the lessons.

In the marketing industry, for example, digital makes testing much cheaper and faster. We can now sample a large number of variations of content, quickly get data on what’s working, and choose the best option. Algorithms that learn and iterate over time allow us to do this automatically, and we accept the “wastage” of the discarded options as a legitimate cost for a better outcome.

Similarly, institutions can quickly test policy approaches or communications. The UK government saved £30 million by testing variations of the wording of letters to people with outstanding taxes.

In a fast-moving world, governments will sometimes need to step into the unknown without a historical evidence base. Instead, we need pilots and tests that can quickly determine whether a policy is working and how to improve it (and, hardest of all, thicker skins when the brickbats start flying).

Administrations need to be confident enough to innovate in other ways, too. Rob Norman, chief digital officer of WPP’s media investment management arm, GroupM, makes a powerful case for the adoption of audience buying or behavioural advertising techniques by governments.

Audience buying uses online behaviour to provide consumers with relevant content online and, says Rob, “can enable governments to find and target their audiences with greater precision than ever before.”

He points to the Dutch government’s recent campaign to educate holidaymakers about customs regulations. The campaign tagged users of holiday booking websites and then served them humorous videos reminding them not to bring certain items back into the country.

Audience buying is still a relatively new business model and industry and governments will need to work together to overcome the challenges this presents, but, to quote Rob again, it’s “one of the practical applications of big data that is established and works… [which] could make it an interesting sandpit for governments to trial new approaches.”

- Focus on the plumbing, not the water

In a digital world, platforms are very powerful.

Some of the most successful digital businesses are those that provide a platform for others to operate: social media like Facebook or Twitter enable people to connect and communicate; eBay enables people to trade; Deezer and Spotify enable people to discover and play their favourite music; Google enables… well, just about everything.

None of these businesses produces goods or content (with the possible exception of Google, given its foray into wearable tech and driverless cars). But they are hugely valuable because they provide the right environment and ecosystem for others to flourish.

The best e-government will learn from this approach. Governments should provide a backbone of infrastructure, technology and data that enables citizens, NGOs and businesses to innovate and participate. The UK, for example, has put the idea of “government as a platform” at the heart of its new digital strategy.

In Sweden the SMSLifesaver initiative is a perfect example of government acting as an enabling platform. It allows trained citizen volunteers to enrol to receive a text message when someone suffers a heart attack in their vicinity, so that they can respond and help – often faster than the emergency services. In the last ten years Stockholm County has seen survival rates after cardiac arrest climb from three per cent to nearly 11 per cent.

Returning to the subject of Google doing pretty much everything: there’s a section of its business site called “Apps for Government” with a page headlined “Governments in 45 states have gone Google.” Beneath this is a range of case studies describing how various US public bodies – from the State of Maryland and the City of Boston to the US Army and the National Archives – are using Google as a platform in one form or another. Powerful indeed.

- Bring code into the classroom

Businesses, governments and populations in general need better digital and programming skills. In the modern marketing services industry, for example, it’s just as important to recruit Maths Men as it is Mad Men.

The US Department of Labor estimates that by 2020 there will be 1.4 million jobs in computer sciences, but only 400,000 graduates with the qualifications to fill them. Other parts of the world will see this as an opportunity, but only if they have the right educational programmes in place.

According to Stanford researchers the number of computer science and engineering graduates from the elite Chinese universities is more than the total number of such graduates – from all universities – in the United States.

Some argue that this extraordinary statistic comes at the expense of China’s second-tier universities and graduates, and thereby the wider economy, but it’s a stark reminder of the rising power of the People’s Republic nonetheless.

Partly in an effort to compete with fast-growing economies like China and India, England recently made coding a mandatory part of the curriculum.

From September 2014 children as young as five began learning programming skills in the classroom. By the age of seven, all English children should know what an algorithm is and how it works – making them considerably better informed than the large majority of the adult population.

Whether or not this helps the UK to overhaul the lead established by its Eastern competitors remains to be seen, but it’s a long stride in the right direction – one that I expect to be replicated elsewhere in Europe, and beyond.”